There is something so enlightening in discovering an unknown facet of an artist, especially when one has known them for other mediums and art forms. In their artistic pursuits, people can be extremely multi-faceted, yet some of those sides seem to eclipse others the moment they achieve fame for their work in a specific area.

American painter Cy Twombly is well-known for his painting style of lines, scribbles of words, and poems on large canvases. He battled years of eye-rolls and criticism for his highly expressionistic perspective on art in a time where color and bold representation were all the rage, led by the Pop Art movement. He finally achieved recognition for his work in the latter half of his career after more than 30 years of devotion and dedication to representing sensibility, sensuality, and emotion.

While studying at the Art Students League in New York in the early 50s (where he met Rauschenberg and where the two became inseparable), Twombly also became interested in photography and began taking/making photographs with a pinhole camera. In the following years, he would photograph some of his friends - Franz Kline and John Cage at Black Mountain College - and the objects and things he would encounter while traveling.

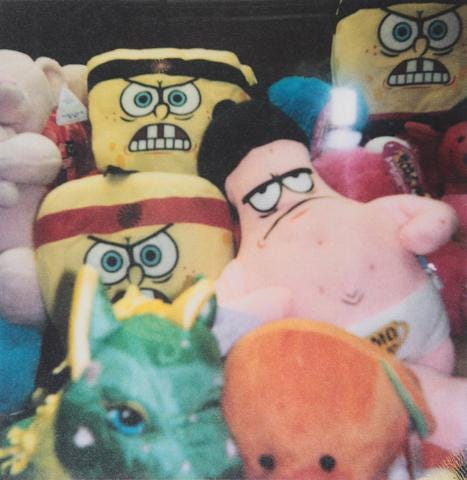

The scrawls, scribbles, and ripples of his paintings attempted to retain a particular moment in time, and his photography tried to do the same. By using a tool so rooted in immediacy, he was able to inform his art and record the work-in-progress in his studio, but also to preserve the fleeting details, memorabilia, and lightplays that surrounded him. The textures and light were what interested him the most. In his Polaroids, objects aren’t often shown as a whole but as details and parts of something larger with its own consistency and nature, locked in a moment in time: the roughness in the skin of a lemon, the little scabs of dried paint in a brush.

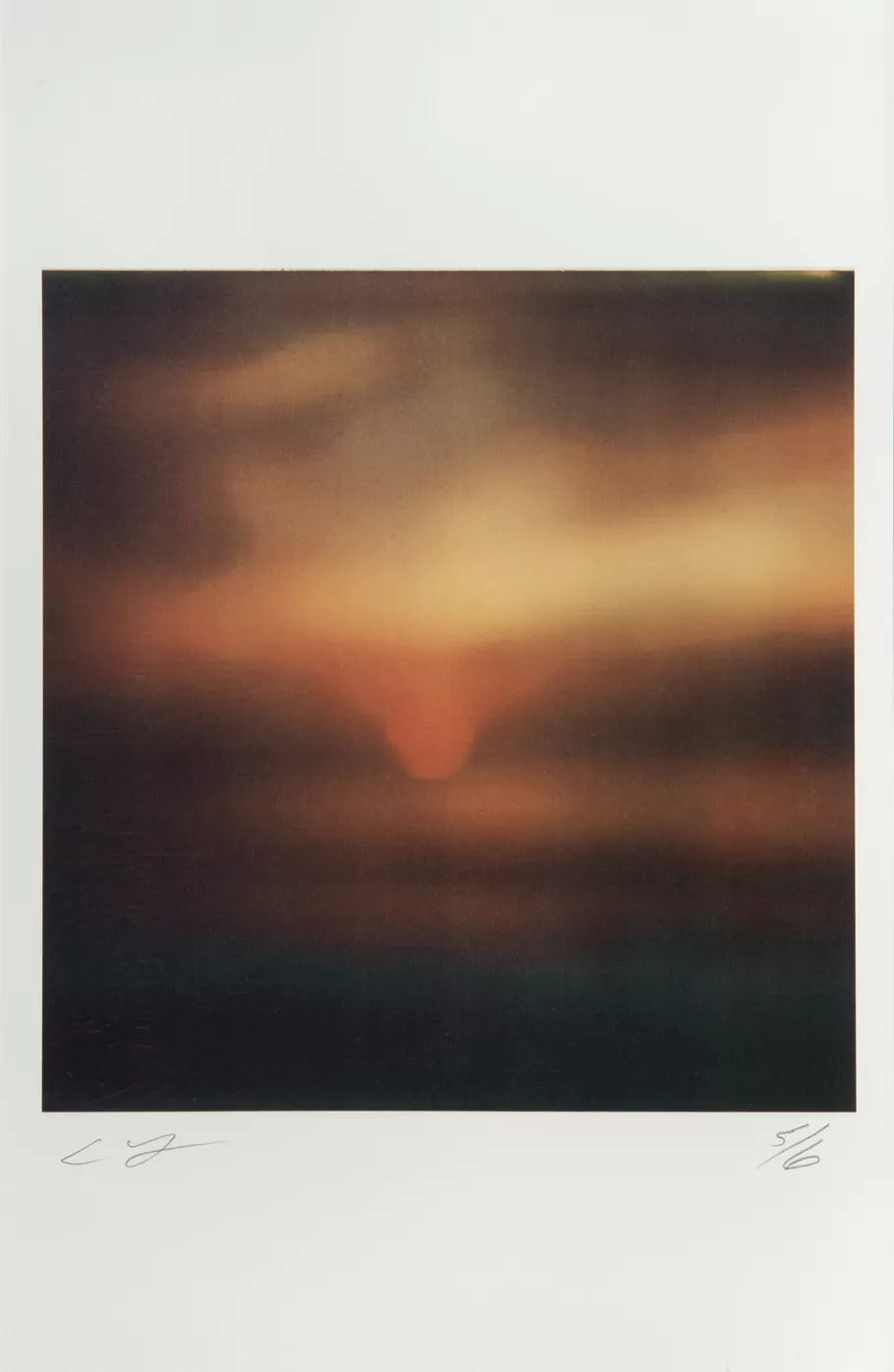

This magical, almost out-of-earth feeling that his photographs evoke isn’t just his talent but the printing process they’ve been through, called Fresson printing. The technique was developed by a French family in the end of the 19th century, and has been handed down from one generation to the next, keeping some of the elements of the process secret and making Atelier Fresson (in the outskirts of Paris) the only place it can be done.

Fresson printing makes mood and character a priority, emphasizing light and texture in a way that no other photography printing process does. Colors are fretted, blended, profounded, and the results look like rich, moody pastel drawings that have stoically survived the test of time. Not much is known about the process, but the most fascinating thing is how reliant on chance the whole thing is, depending greatly on the conditions the photograph is manipulated in and on the experimentation of the people who work on it. It takes them around six hours per print, and they only make about two thousand prints a year for some of the most celebrated photographers of our time, like Sarah Moon or Sheila Metzner.

The Fresson family has stuck to their old ways of running their business and to their 2000s website, which harks back to the early days of the Internet. A few tabs, a salmon background, a serifed font, a main navigation with pages that change color once clicked. Unexpectedly, there is something very comforting and familiar about it, much like in the photographs they produce, which resemble paintings more than photographs. It’s the same familiarity that runs through Twombly’s polaroids, in the everyday objects they represent, and in the ordinary beauty of the crinkles of a cabbage and of the folds in the petals of a tulip.