On Maison La Roche, Purism and Gifting Cars

How one of the most famous Modernist buildings came to be.

One summer day in 1918, a group of Swiss expatriates living in Paris met at the so-called Déjuner Suisse. One of the attendants was a young architect and painter named Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, who two years later would adopt the name with which he would become famous: Le Corbusier. Through a common friend, Jeanneret was presented to banker Raoul La Roche, a wealthy young Swiss working at the Crédit Commercial de France, one of the largest banks in the country. The two got on surprisingly well and would establish a lifelong friendship in the following years that would result in the world’s largest collection of Cubist art and the commission of Maison La Roche, a gem of the modernist movement.

At the time, Jeanneret was developing his first ideas on Purism and worked closely with writer and painter Amedée Ozenfant. La Roche was rapidly taken by the Purist principles of reduced, ‘pure’ forms and simple geometric angles and shapes emphasized through color and decided to start his own art collection. His first purchases where the Flacon, guitare, verre et bouteilles à la table grise by Ozenfant, and Composition à la lanterne et à la guitare by Jeanneret.

His interest in Purism wasn’t only crucial for the development of the movement in itself but for the development of art history. In the words of art historian Franz Meyer, ‘If in 1920 you gave yourself the brief to build a museum collection of Cubism and Purism out of the important works of Picasso, Braque, Gris, Léger, Lipschitz, Le Corbusier, and Ozenfant you could hardly have chosen in any other way than he [La Roche] did. In 1920 there were no curators and no commissioners who could tell you which pictures should have a place in a museum’.

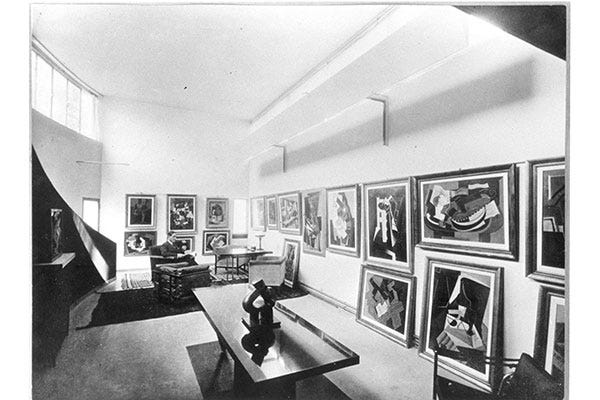

La Roche had a great eye for art. He also had incredible luck. In 1921, eight hundred Cubist paintings by Picasso, Gris, Léger, and Braque entered the Parisian art market. The paintings belonged to a German art dealer and were confiscated back in 1914 by the French government as enemy property. They were sold in four auctions between 1921 and 1923, and Jeanneret and Ozenfant acted as his bidders, acquiring, for a relatively cheap price, a selection of some of the most important works of the period. La Roche’s art collection was rapidly expanding, and his small flat overlooking the Champs de Mars was not fit to house it. It was then that he commissioned Jeanneret to build a villa for him.

Maison La Roche-Jeanneret is one of the famous ‘purist’ villas built in Paris from 1920 to 1930, a hidden treasure in the sixteenth arrondissement. To access it, one must take a private roadway off the Rue du Docteur Blanche, arriving at a small square.

Surrounded by tall bourgeoisie buildings, Maison La Roche-Jeanneret is a ‘stony hued’ (in the words of Le Corbusier himself) short and elongated building, with clean lines and simple forms, composed of two semi-detached houses. One of the houses was meant to accommodate La Roche and his collection, the other Jeanneret’s brother and his family. Today, Maison Jeanneret contains the offices of the Fondation Le Corbusier. Maison La Roche is the one that can be visited.

When Jeanneret secured the site in 1920, he needed to compromise on certain elements: the available land was very limited, and height restrictions were set. Other buildings surrounded the plot, and Jeanneret had to build a square to access the house from the main roadway. However, he was able to build the house as he intended and preserve the integrity of his original design concept.

The use of new building materials at the time, like reinforced concrete, allowed Jeanneret to start playing with what he would later call the Five Points of Architecture, a series of architectural principles that prioritized the use of pilotis (columns), an open floor plan, a free façade, horizontal windows, and a roof terrace. He would use these principles as the basis of his designs and as underpinnings for his urbanism theories, which he would later apply when working on a committee for the Vichy Regime that collaborated with Nazi Germany during WWII.

He made dubious political alliances during his lifetime; some argue that he was constantly cozying up to those in power at the time. Quoting architecture critic Deyan Sudjic here: ‘Le Corbusier was not the first architect to discover that making great architecture depends on a very close relationship between the architect and the rich and the powerful, and in some cases, some unsavory rich and powerful.’

Maison La Roche-Jeanneret also allowed him to put into practice one of his dearest concepts, the ‘architectural promenade.’ The interior of the Maison is arranged around two spaces, one ‘public’ (hall, painting gallery/living room...) and the other one private (bedroom, dining room…), each accessed by a staircase on either side of the entrance hall. Entering the house means committing to an architectural show all the way through. One feels like there’s already an established path that must be followed across the rooms and across the different viewpoints.

A great example is the gallery room that displayed all of the banker’s artwork. It’s a horizontal space that contrasts with the verticality of the previous room, the hall, composed of two floors, connected by an elegantly curved ramp that curls into the hollow of the façade. The ramp invites the visitor to continue the walk around the house and offers new viewpoints and perspectives that bring together interior and exterior, up and down. In his words, ‘Imperceptibly we climb a ramp, a totally different sensation from climbing a staircase made of steps. A staircase separates one floor from another; a ramp connects.’

La Roche fell in love with his new house. In a letter to Jeanneret dated March 13th, 1925: ‘This house gives me great joy, and I convey to you my gratitude. You have brought to completion an admirable work that, I am convinced, will mark an epoch in the history of architecture. […] What especially moves me are these constant elements that are found in all the great works of architecture but which one meets so rarely in modern constructions. Your ability to link our epoch to the preceding ones in this way is particularly great. You have ‘overrun the problem’ and made a work of plastic art.’

In a gesture of gratitude and to supplement the price of the villa as it ‘cannot be calculated,’ La Roche bought him a 5HP Citroën.